The 400 Series of Highways:

The rise of the automobile as a common sight in Canadian households put pressure on infrastructure throughout the country. While the automobile was more of a luxury than a necessity until the Second World War, newfound prosperity from wartime production needs and mass enlistment in the Canadian Armed Forces – alongside postwar veterans’ benefits – made the automobile a possibility for many families. Policy-makers in Ontario started looking for solutions in the 1930s, but it was post-war investment in infrastructural development that motivated the Progressive Conservative government of George A. Drew to announce plans for a series of four-lane highways connecting Ontarians from east to west and from north to south in November 1943. The Queen Elizabeth Way, the 401, and the Toronto-Barrie Highway – later called the 400 – were the main arteries to be integrated into the 400 series, which has grown to a series of 15 highways. The Queen Elizabeth Way, which emulated German Autobahns, was the first divided highway to open in North America in 1937, however, it was not a true freeway until the 1950s. The first 400-designated highway, the Toronto-Barrie Freeway, opened on 1 July 1952.

Tourism and the 400:

Barrie served as a major stopover on Torontonians’ common trips to cottage country. During the 1930s and 1940s, a wave of city dwellers began purchasing land and constructing cottages in Muskoka in an effort to escape the city during their leisure time. Labourers had gained during the Second World War, receiving higher wages, shorter work weeks, and longer vacation times, adding to the enthusiasm for tourism and leisure properties. Simcoe County was a hub for fishing, water sports, and other outdoor activities for those on their way to Muskoka or just looking for a getaway. To get from Toronto to Barrie, travellers could choose between the historic Highway 11 or the newer Highway 27, but both routes made their way through several towns and, ultimately, Five Points in downtown Barrie. By the 1930s, citizens of Barrie and travellers alike were clamouring for relief from the weekend congestion, which came to a head on holiday weekends, especially Dominion Day.

Holiday Weekends in Downtown Barrie:

Traffic became a major concern for Barrie during the 1930s. While business owners welcomed the increased traffic from out-of-town visitors and passers-by, the congestion became overwhelming. On Monday, 2 August 1937, traffic crawled through the downtown core, with 4,000 cars passing through the Five Points each hour. Pedestrians might have had to wait for half an hour to cross the road and Barrieites could hardly navigate their town streets. Business owners may have been overjoyed, but, to their chagrin, plans were underway to carve a new path around the town, bypassing Allandale, Barrie, and Orillia. In the meantime, with car ownership increasing year over year, Barrie’s downtown core endured the yearly congestion or official holidays. By the late-1940s, holiday traffic could stall as far away as Stroud on Highway 11 and it might take close to an hour to travel two short miles in town.

Building the 400:

Construction began in earnest in 1945, with grading from the southern tip (at present-day Black Creek Drive) to the junction with Highway 27 completed by 1947. The bulk of the work, however, was poured into cloverleafs and overpasses, which took a combined three years to complete. Further work to extend the grading to Highways 93 and 11, alongside the surfacing of the highway, were completed along a similar timeline. On 1 December 1951, the Toronto-Barrie Highway opened to traffic, with one lane headed in each direction. The ribbon cutting on 1 July 1952 officially opened all four lanes to north-south traffic and immediately alleviated the bottleneck in downtown Barrie. It also reduced the commute from Toronto to Barrie to under an hour, bringing with it the possibility of Toronto workers moving north to escape the city.

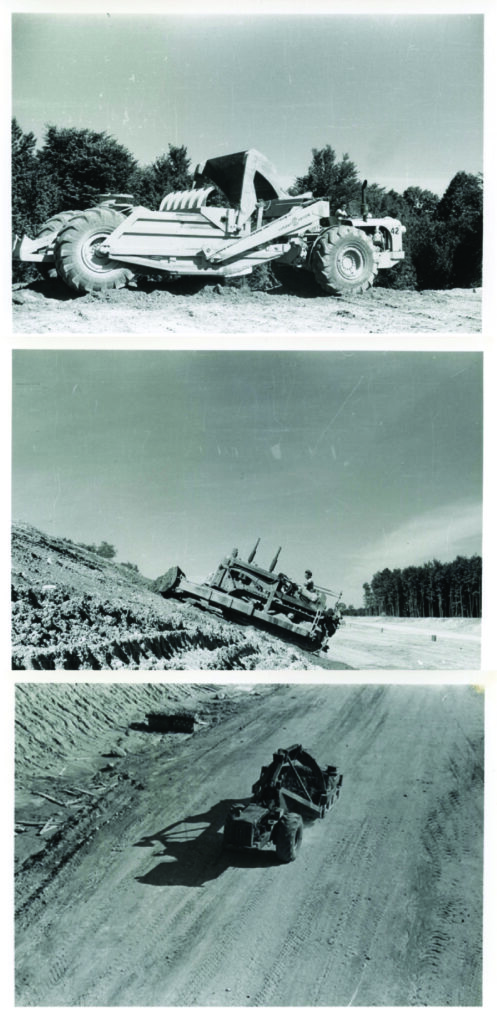

(Middle) Norman Clarke, Bulldozer on Angle Highway 400, 1951, Simcoe County Archives.

(Bottom) Norman Clarke, Earth Scraper Working on Highway 400, 1951, Simcoe County Archives.

Earth Movers, Graders, and Pavers:

When the work began on the Barrie to Toronto highway, an impressive and diverse collection of heavy machines were mobilized to complete the work. Earth movers and earth scrapers helped trod the path from the south end of the highway to the southern reaches of Barrie by 1947. Bulldozers then carved a clearly defined path bypassing major towns, including Barrie. Once the route was ready, around 1947, pavers moved in to give the roadway a smooth surface for travellers headed north and south along it. With many men returning from the Second World War looking for work and governments across Canada trying to avoid sinking into another depression like that of the 1930s, massive projects like the 400 Highway helped keep the economy moving, both by putting people to work on their construction and feeding growing industries like tourism, which thrived amidst post-war prosperity.

Tracing an Ancient Route:

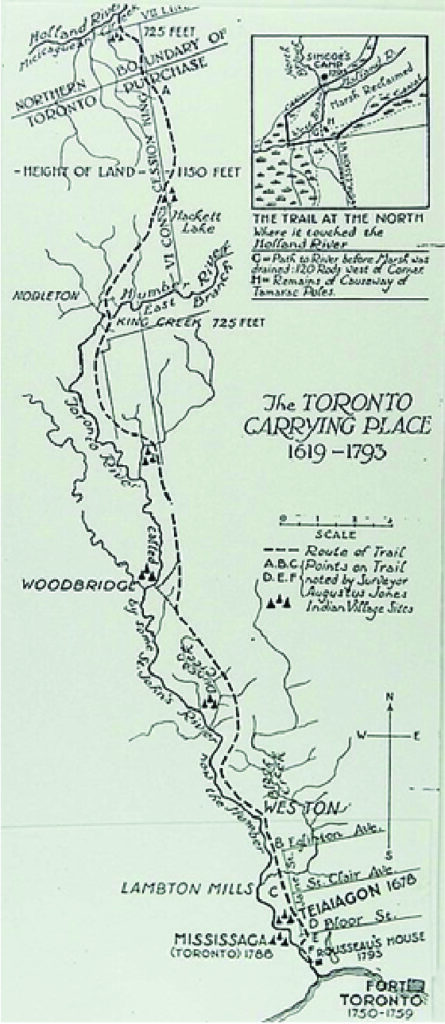

Before its use as a ‘Holiday Highway,’ the course the 400 traced from Toronto to Barrie was an important route from the Lower Great Lakes to the Upper Great Lakes. The inhabitants of Simcoe County at the time of European contact, the Wendat, utilized a portage – the Toronto Carrying Place – that began at the mouth of the Humber River and ended at the Holland River, opening access from Lake Ontario to Lake Simcoe, which then connected to Georgian Bay on Lake Huron. Long used for trade amongst Indigenous peoples in present-day Ontario, the Toronto Carrying Place played a role in the Fur Trade, where the Wendat served as middle-people between Anishnaabe hunters and European traders. When the Wendat retreated from Simcoe County in 1649-1650 in the face of epidemics and attacks from the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the route continued to be trodden by Haudenosaunee warriors and traders, as well as Europeans making their way from present-day Toronto to the rich beaver hunting grounds to the north of Simcoe County. The Mississauga, an Anishnaabe nation, then inherited the Toronto Carrying Place after the Haudenosaunee retreated from the area at the turn of the 18th Century. Until 1793, the Toronto Carrying Place remained in use and spots along the original trail are still traceable today.

The Early Years of the 400:

The 400 certainly lived-up to its moniker as Ontario’s ‘Holiday Freeway.’ When the automobile made its way into more and more households, the vehicle itself became a form of leisure. Throughout the 1950s, Ontarians took to new roads to enjoy fresh air, roadside entertainment, and distant towns that they could not have easily reached before. Along the route from Toronto to Barrie, savvy entrepreneurs sold drinks, snacks, and other wares along the side of the highway. Some travellers might pull into the grassy middle divider between the northbound and southbound lanes to enjoy a picnic and rest. By the 1960s, rest stops and roadside attractions became part of the journey, but drivers and passengers alike simply enjoyed being on the road with the fresh country air.

Barrie as a Commuter Town

In 1945, General Electric announced that it would open a factory in Barrie, signalling the town’s growth as a manufacturing centre. Getting goods to market was no doubt made easier by the reduction of the trip from Barrie to Toronto to under an hour. But many people who worked in Toronto started to move to the suburbs to escape the perceived dangers and cramped living quarters to which city dwellers had become accustomed. The suburbanization of Canada during the 1950s and 1960s followed North American trends, with nuclear families choosing to live in safe, enclosed communities with easy access to the outdoors and the city. The backyard was the favoured retreat, while the television was the centrepiece inside by the mid-1960s. Barrie ballooned alongside industrial production, suburbanization, and the easier commute down the 400, growing from 10,633 in 1945 to over 21,000 in 1960.

Routes, Waterways, and the History of Simcoe County

Pre-dating European contact, the geographical realities of Simcoe County made it a strategic area to control. The Toronto Carrying Place, which has archaeological evidence along its course dating to 10,000 BCE, is the first evidence that the route from the Lower Great Lakes to the Upper Great Lakes was essential to life in present-day Ontario. The settlements of York and Kempenfeldt, later renamed Toronto and Barrie respectively, built upon nodes of the Carrying Place and helped European fur traders navigate existing Indigenous trade networks, which also included the historic Nine Mile Portage that cut east to west from Lake Simcoe to Georgian Bay. The 400 carried on the tradition, if unwittingly, by following a sensible geographic route from Lake Ontario to Lake Simcoe en route to cottage country.